In art education, it’s easy to get caught up in grading the final product. But as teachers, we know the final artwork is just one part of the story. Growth happens throughout the process—through trial and error, creative risk-taking, and especially through reflection. Not every student who walks into the art room is passionate about art or naturally skilled at it. Some are determined and resilient. Others only engage deeply when they connect with the project. Many can express their ideas clearly in writing or discussion, but struggle to translate those ideas into visual form. That’s why it’s important to offer students a second chance. In most subjects—and often in art as well—students don’t get the opportunity to revisit their work and show how they’ve grown. But when we give them that chance, we affirm that learning is a process, and growth deserves to be seen, supported, and celebrated.

Why Allowing Students to Redo an Art Project is Good Teaching

Some parents and teachers may worry that allowing students to redo assignments suggests that the teaching wasn’t effective the first time. This concern is understandable, but it misses the purpose of the practice. Redoing a project doesn’t mean the first round was a failure. It means students are ready to apply what they’ve learned, think critically about their choices, and demonstrate meaningful growth.

When students redo a project, they are not just repeating—they are reflecting, problem-solving, and challenging themselves to do better with the skills they’ve gained. Reflection gives us a fuller picture of student learning. It tells us not just what students made, but what they learned, how they thought, what they struggled with, and how they grew. As educators, it’s important to assess more than the final result—to recognize growth, effort, and problem-solving.

When and How to Introduce the Redo Assignment

The redo project works best when assigned at the end of the school year, as a culminating task. Students revisit one of their earlier projects and create a new version using the same techniques but with a different subject or concept.

To keep expectations clear and focused on learning, the teacher may pre-select or limit which projects students can choose to revisit. This ensures that students are engaging in meaningful reflection rather than choosing the simplest project for an easy grade boost.

A Second Look: One Assignment, Two Versions

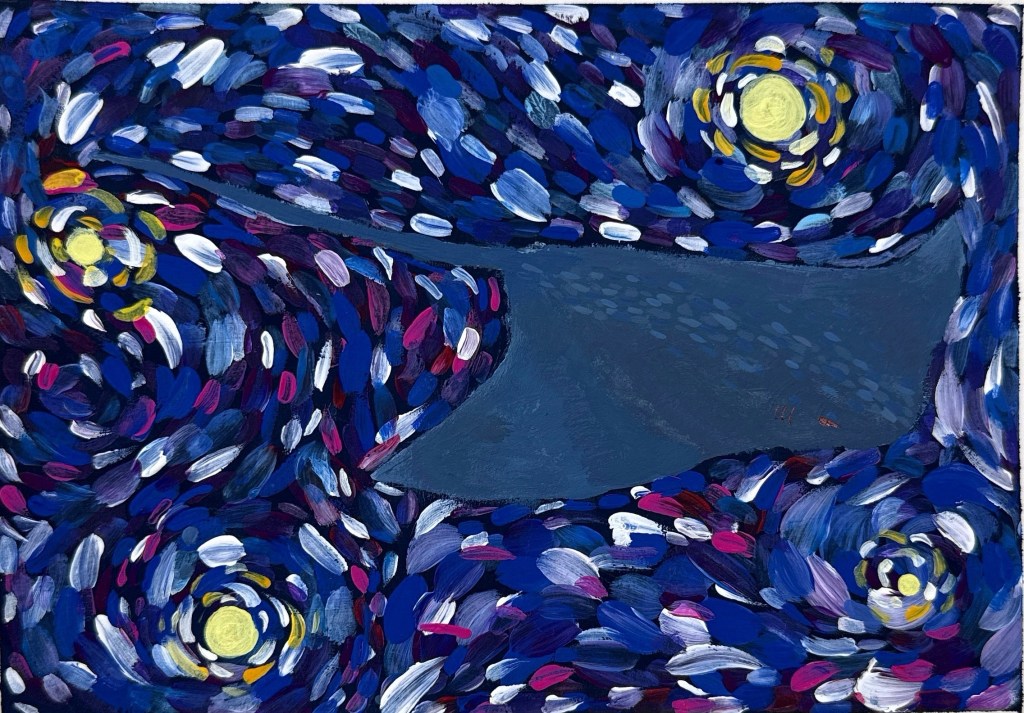

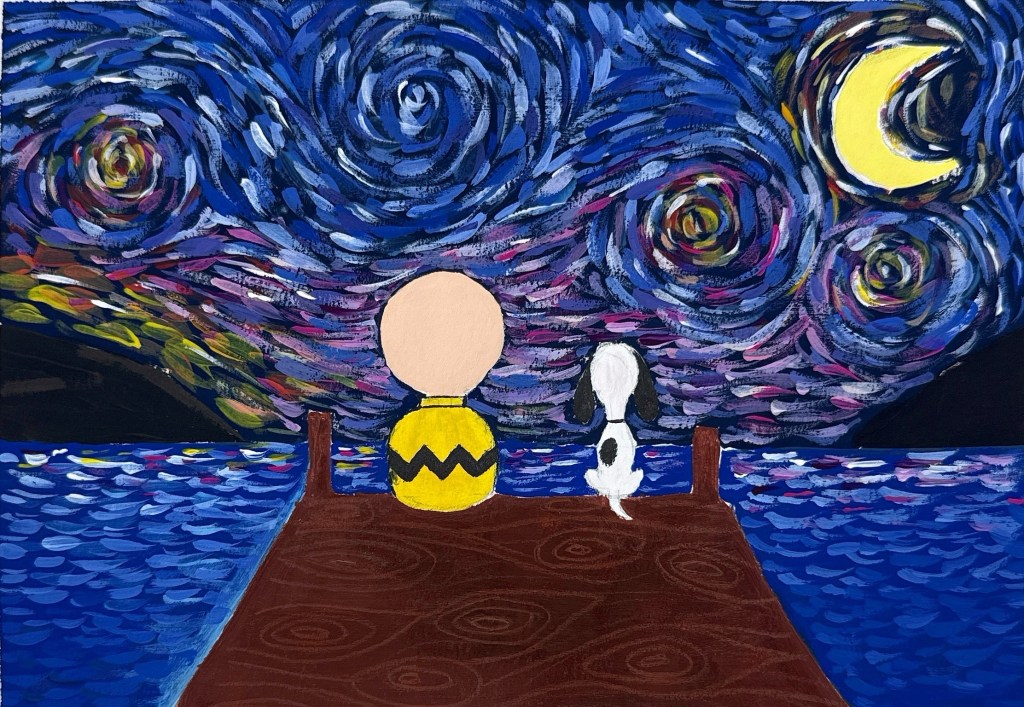

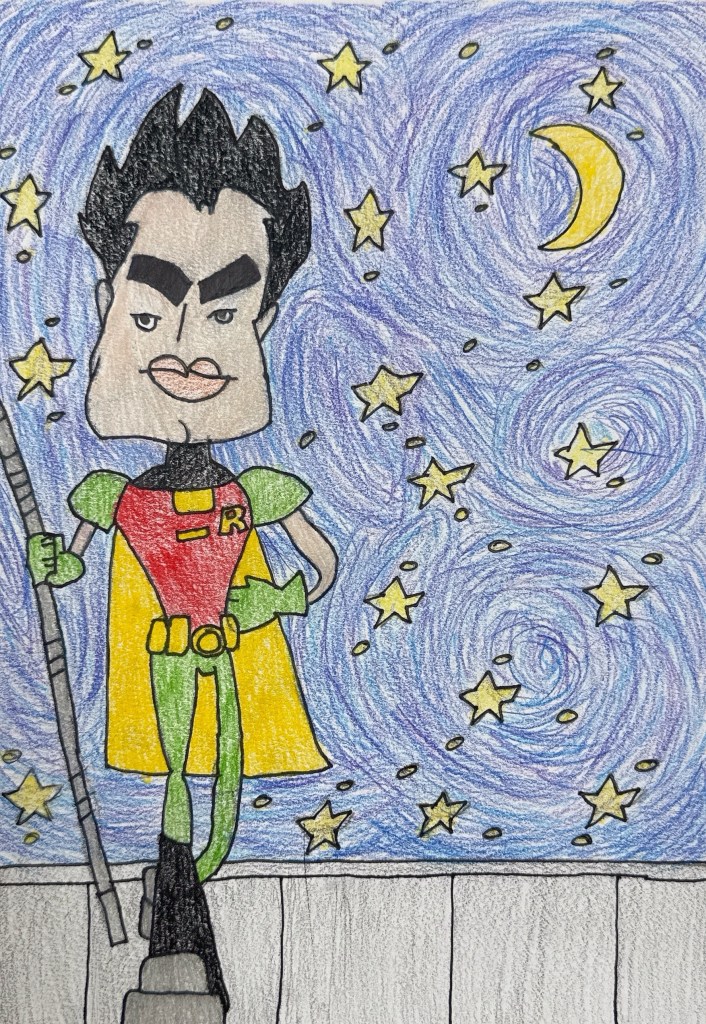

To meet the Ontario Curriculum’s requirement for cumulative practical tasks, I asked my students to recreate one of their major projects from earlier in the year, using the same techniques but with a new subject or vision. Many chose to redo their movement project, originally inspired by Van Gogh’s Starry Night.

Original Assignment Recap:

Challenge:

- Capture movement using short, expressive strokes

- Use Van Gogh’s iconic color palette

- Reimagine the scene in a personal way — a cityscape, forest, or underwater world

Goal:

Create a dynamic piece that showcases understanding of movement, composition, and color theory while making it your own.

This time around, they had creative freedom, a chance to apply new skills, and a fresh perspective. Maybe it was the motivation to raise their grade (I don’t blame them!), or maybe the open-ended topic gave them more room to express themselves. Whatever the reason, the results were astounding.

What Reflection Uncovered

By comparing their first and second versions, students developed critical self-awareness and a sense of artistic growth. Here’s what emerged through their reflections:

1. Increased Confidence

“Now, I would gladly choose to do another movement piece and I would happily enjoy it.”

With prior experience under their belt, students approached the same techniques with less hesitation. They were braver, more experimental—and it showed.

2. Visible Improvement

“In my second project, it looked a lot cleaner and had more smaller swirly movements instead of one big circle.”

Students could clearly articulate what had changed and improved. From better planning to refined brushwork, the differences were meaningful.

3. Greater Enjoyment

“Going with the flow made me dislike my coloring artwork, but helped me enjoy painting more.”

The medium mattered. Several students realized that using paint—something they may have previously avoided—was not just doable, but enjoyable.

4. Creative Problem-Solving

“One of the biggest issues was that I accidentally smudged some colors… I embraced the smudges and incorporated them into the design.”

This is where growth really shines—not in avoiding mistakes, but in learning how to adapt when they happen.

5. Sense of Accomplishment

“I realized it looked a lot better than the first one because in the first one I didn’t know how to apply this technique properly.”

These reflections were full of pride, not perfection. That’s the true mark of meaningful learning.

Why Reflection Matters—Even When the Results Don’t Feel “Better”

While many students created second versions that were technically stronger, not everyone walked away loving their new piece more. And that’s okay—that’s where the real learning begins.

One student, in particular, stood out during this assignment. Her first piece was beautifully rendered and emotionally resonant. It captured movement and color in a way that felt effortless. She was proud of it—and rightly so. But when asked to do the project again, something changed. She became hesitant, even anxious.

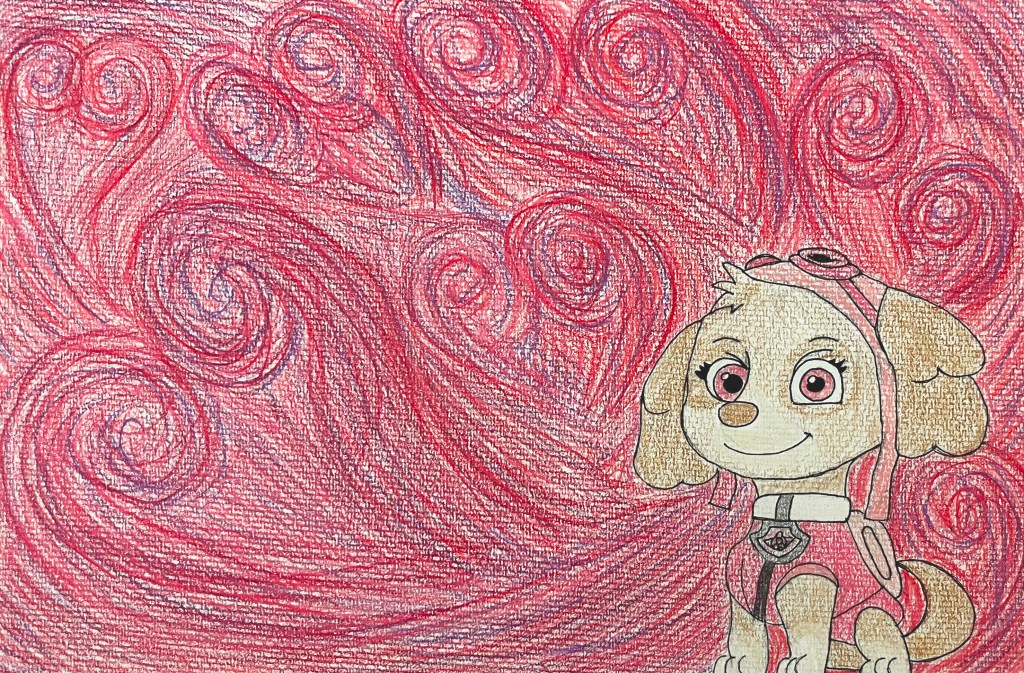

She started with an exciting idea, planning to draw Skye from Paw Patrol using Van Gogh’s swirling movement technique. But then, self-doubt crept in. She worried that her second piece wouldn’t live up to her first. She questioned whether her first success had been a fluke. Was she really “good at art”—or did she just get lucky?

“Because I liked my first piece so much, I kept comparing it and didn’t like the outcome of my Skye from Paw Patrol art as much as my Snoopy one.”

What she experienced is something every artist, beginner or professional, goes through: the fear of not being able to replicate success. The pressure of high expectations, especially our own, can be paralyzing.

Yet when we look beyond the finished product, we see something far more important—growth in process, skill, and self-awareness.

Here’s what she wrote in her reflection:

“I was proud of this specific part of my art because compared to my reference, it’s very accurate… Before this project, I didn’t know that I was able to draw accurately from a reference.”

“To make this artwork more interesting from my first, I decided to use two swirls to make a heart… It added a unique feature that catches people’s eyes.”

Even though she preferred her first piece, she showed clear evidence of:

- Applying new techniques (color layering, controlled strokes)

- Taking creative risks (adding a symbolic heart shape)

- Problem-solving (figuring out stroke direction for motion)

- And, most importantly, honest self-reflection.

These are not just art skills—they are life skills.

The Artist’s Mindset: Learning From the Inside Out

Art is deeply personal. It’s also unpredictable. You don’t always know how something will turn out. But through reflection, students develop the mindset of a true artist:

- They learn to navigate self-doubt.

- They begin to separate the process from the product.

- They build resilience by revisiting challenges with new tools and insights.

Some reflections celebrate victory. Others reveal inner struggle. Both are valid. Both are valuable.

Again, art isn’t about perfection. It’s about progress. Let’s celebrate the moments when students are brave enough to try again—not because they’re guaranteed to succeed, but because they’re open to learning more about themselves in the process.

Leave a comment